WALK-INS WELCOME

//

WALK-INS WELCOME //

WALK-INS WELCOME uses the common message found on nail salon windows, transforming Vietnamese women’s presumed readily available service labor to push for alternative investments and redistributions towards community care.

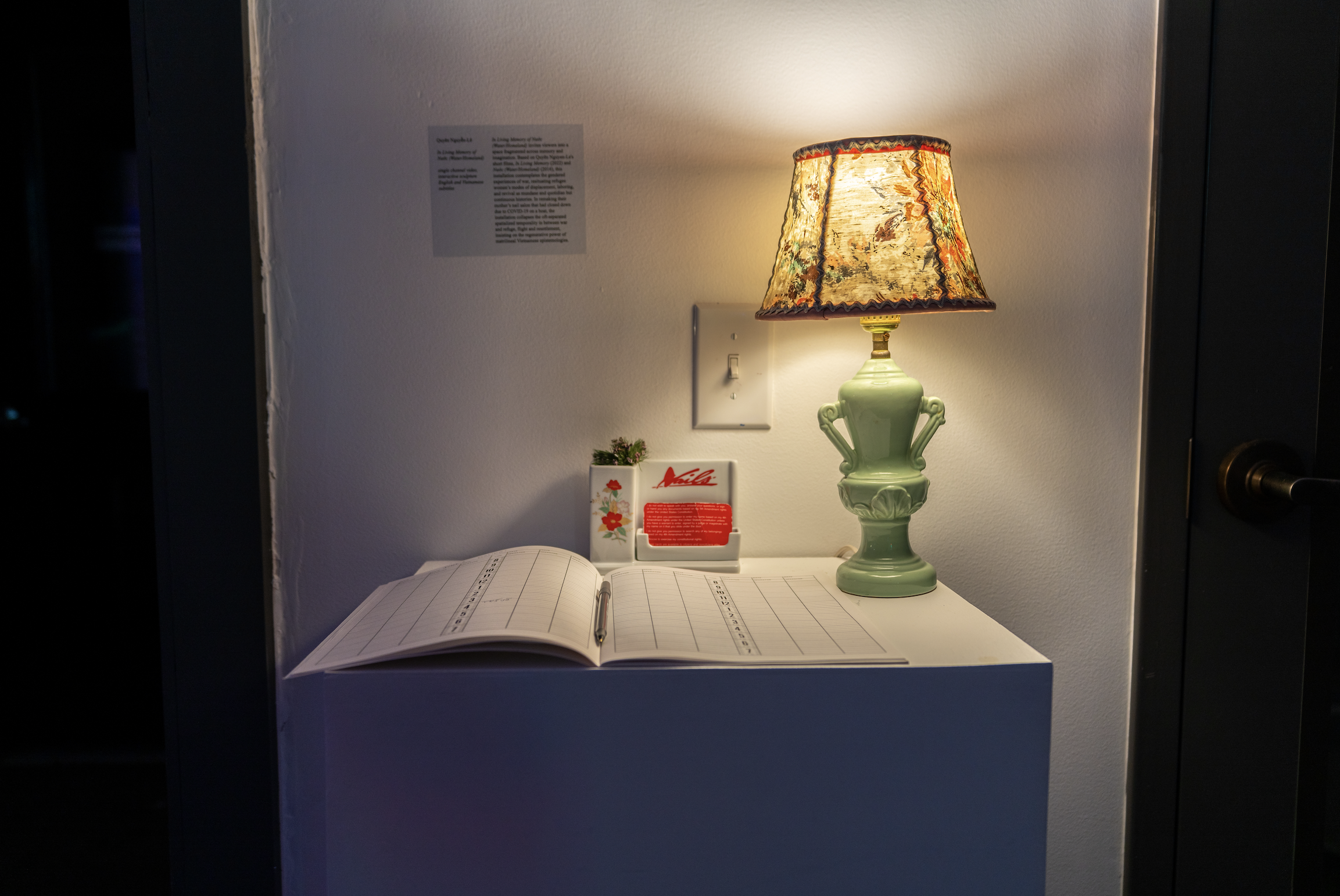

Quyên Nguyễn-Lê

In Living Memory of Nước (Water/Homeland)

single channel video, interactive sculpture

English and Vietnamese subtitles

In Living Memory of Nước (Water/Homeland) invites viewers into a space fragmented across memory and imagination. Based on Quyên Nguyen-Le's short films, In Living Memory (2022) and Nước (Water/Homeland) (2016), this installation contemplates gendered experiences of war, and resituates refugee women’s modes of labor as both quotidian and continuous histories. In remaking their mother’s nail salon on a fishing boat, the installation collapses the oft-separated temporality in between war and refuge, fleeing and resettlement, insisting on the regenerative power of matrilineal Vietnamese epistemologies.

‘I learned a lot about my family history through sitting in that nail salon and listening to my mom and her co-workers speak,’ Nguyễn-Lê said. ‘It’s not like they sat there, did nails and talked about the war, but over time, you catch fragments and the story kind of comes together.’

The expression directly resists the regulatory infrastructure of settlement/colonization—identification checkpoints, border zones, detention camps, resettlement agencies, welfare offices, prisons, and racially segregated housing and schools—that continue to contain and separate refugee lifeworlds for ongoing dispossession and exploitation.

INFRASTRUCTURES OF FEELING

//

INFRASTRUCTURES OF FEELING //

Christina Hughes

INFRASTRUCTURES OF FEELING invites visitors to travel with the artist across an array of seemingly disparate sites of memory. Sensitive to the lurking affective mobilizations laying dormant within the haunted landscape, the works collectively gesture to intergenerational and intimate encounters with mundane military-industrial formations found across Southern California. Highlighting a network of sites, technologies, and assemblages of defense-related infrastructure that shape and privatize our modes of communication — particularly across prison walls — the pieces concern themselves with the how the taken-for-granted grounds on which we travel dissimulate the settler condition of the nation and the hypocrisy of the carceral state in claiming moral authority over the racially criminalized.

Christina Hughes

a soft corrosion

mixed-media installation

second-hand yarn, concrete cinder blocks, steel phones

The work references the feminist craft use of guerilla yarnbombing in order to soften hostile spaces of state enclosure, surveillance, and predatory inclusion. Taking up crochet as a feminist methodology to consider what might be communicated, felt, and learned through embodying its particular labors, a soft corrosion makes room for the affective seepages that cannot be contained—produced from what remains unresolvable and enduringly grievable between Vietnamese refugees and their children, and embracing as politically urgent the overwhelm of memories too difficult to revisit and the impossibility of neatly accounting for all that has been lost.

Christina Hughes

terra nullius // terra communis series

photographs printed on paper; cobalt paint

First: trespassers will be prosecuted; Second: conflicts of interest

Taken in the wake of the ideological Cold War that saw the partition of North and South Viet Nam along the 17th parallel, the photo sets consider the colonial principle of terra nullius—which treats ‘wild’ or ‘insufficiently’ used lands as available for claiming based on the fiction of pristine, uninhabited nature—alongside the principle of terra communis—an assertion of communal ownership of ‘semi-wild’ lands in the name of common stewardship and responsibility.

The images question the landscape as a neutral space, unsettling national-state claims to border sovereignty and legal authority by threading the palimpsest grounds on which the artist’s familial biography has traveled and which themselves mirror the wry irony of ‘refugee rescue’ (and refugee deportability) on stolen land.

a soft place to land

discarded yarn threads and found fabric

Made from collecting the stray threads produced from a soft corrosion, a soft place to land gestures to the technology of the scrap bag in order to imagine alternative sites and landscapes that emerge from where the forgotten, overlooked, devalued, and discarded create vital geographies of mutual rest and reprieve. Playfully, it acts as a textural counter to the rigid materiality of the prison and the border wall, inviting forms of abolitionist worldbuilding couched in softness as not only an aesthetic but also a relational political practice with durable possibilities.

RE/HOMING materializes spaces that are real and imaginative to receive and make homes for the discarded-yet-grievable lives, littered in the wake of masculinist war and nation-building and washed ashore, unable to be captured or co-opted by dominant commemoration regimes.

Motherlands

//

Motherlands //

Ly T. Nguyen

MOTHERLANDS shows an impressionistic pocket of homeland condensed in the overlay of rarely-visited dark rooms in the artist’s memories and extrapolations: altar rooms, elderly women’s living quarters, a spare room with no window in an ancestral house in Nghe An, single rented rooms occupied by city dwellers, all leading to a courtyard with a multi-purpose water basin that holds and washes living and dead things—a prevalent item in most Vietnamese households that would soon be replaced by indoor kitchen sinks and bathtubs in the shrinking spaces of the expanding cities.

Threaded through the illegible feminine matters of fallen hair and jagged nails, this installation attempts at materializing a relationship across four generations of exilic women who were daughters of daughters who left their land of birth. The pieces contemplate the growing life forces that evidence both vitality and agedness, which remain constant across space and time but become monstrous without attachment to the racialized feminine body. Imbued in these pieces is a queer longing for a maternal lineage that resists disposability, remembers queerly, and exerts bodily autonomy—especially against repressive cultures and state effacement.

Ly T. Nguyen

under her nail beds

mixed media installation

hand sculptures: plaster cast on alginate, acrylic, watercolor; wooden altar; mosquito net canopy: polyester; wood carved nail clipper, beige cotton drop cloth

under her nail beds prays to the normalized private pain endured by generations of Vietnamese women who labored at the behest of the multiple colonial and imperial powers that continuously waged wars on Vietnamese territories: Chinese imperial, French, Japanese, and American forces. This pain is symbolized by the small cuts the artist encountered on their maternal grandmother’s nail beds, in the dark bedroom where she would spend the rest of her days. Near the end of her life, Ngo Thi Nguyet (1925-2011), a revolutionary woman, a matriarch mother of five, an organizer for the Women’s Unions and at grassroot levels, a poultry farmer and gardener, was mostly immobile and alone, cared for mainly by a hired nurse—another elderly woman. Unlike her decorated husband with streets named after him, Nguyet’s story quietly withered into obscurity. Her fingers, after decades of knitting and laboring, became injured and paralyzed, unable to feel or see the wounds when the nurse unknowingly clipped her nails too far into her flesh. On that day’s visit, the artist massaged Nguyet’s hands for hours. In the 23 years they shared this earth, this was their longest interaction.

Ly T. Nguyen

something to abandon // đầu cạo sông trôi (*)

video performance filmed in Fort Snelling and Taft Park, Minneapolis

(14 minutes, 02 seconds)

Situated in the first colonial outpost and military base of Minnesota and occupied waterways, something to abandon laces the memories of colonial warfare, incarceration, disappearance, and death against Indigenous populations onto the domestic chores of feminized body management. Head shaving and hair cutting historically are authoritarian and hetero-masculinist forms of criminalization through racialized repression and gendered punishment. Here, a queer embodiment of inscrutability and anonymity embraces this marking of difference, in remembrance of wayward women and in solidarity with interned captives marked for carceral deportation.

* The name đầu cạo sông trôi (head shaved, river flows) subverts “cạo đầu bôi vôi thả trôi sông”—a 19th century Vietnamese punitive practice against unmarried pregnant women. Patriarchal authorities would have the women’s heads shaved and smeared with quicklime, then abandoned to an unmanned bamboo raft downstream. Women transgressing gender and sexual norms, when caught, were exiled from their ancestral home and respectable society.

Ly T. Nguyen

mother’s inheritance // outsiders’ quarters (của mẹ // nhà ngoại)

mixed media installation

water basin, found tree branches, tangled hair bundles, hair strips reassembled from matted hair bundles, hair strips constructed from shaved hair, twines, clear wires

Confucius historiography rules that a daughter is a stranger’s child, and a wife is a family’s outsider. mother’s inheritance // outsiders’ quarters bemoans the pasts and futures that fall out of public and familial knowledge and reconstructs fractured maternal lineages. Through the year-long collection and assortment of hair fallouts into neat bundles, the artist arrives at the tedious process of dematting hair strands by submerging them in hot water and teases out using a needle. Each strand of hair is rescued and examined where it breaks, whether they could be used again, or simply must be discarded. The premise of hair collecting is dedicated to the artist’s childhood of enforced hair growth—an extension or replacement for their mother’s hair and nail breakage due to prolonged undernutrition before and during the postwar subsidy economy.

Nhung Walsh

00;59;01;18 -- "It Was A Beautiful Day And There Was No Fog"

sound file on an mp3 device with headphones, transferred images on a silent tape

"It Was A Beautiful Day And There Was No Fog" are the opening words of a Son My (My Lai) massacre survivor recalling his childhood experience of the event on March 16, 1968. This sound work is an extraction of silences from the interview recording that took place in 2010. By focusing on these ‘interstitial spaces,’ the artist invites listeners to contemplate alternative possibilities outside the fixed historical narrative of what could have happened on that day. This interview was a part of a two-year research project for the book My Lai: Vietnam, 1968, and the Descent into Darkness by Howard Jones (Oxford University Press, 2017). On the silent tape are repeated images taken in March 2025, when the artist took her daughter to feed the pigeons at the Nguyen Hue Square in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 50 years after the war ended. This visit was important for her to continue the conversation about the war with her daughter, as well as to emphasize the extension of the generational (gaps of) memory that comes with time.

Developed in close collaboration, each work tends to the uneven ways ancestral memories and critical knowledges disperse and sprout across homelands and the diasporas: silently embodied and spatialized in generational, gendered, and migrating bodies; laboring through waterways and urban dwellings; and under surveillance and nation-state imprisonment.

N.

Handle with Care

black ink printed on paper made from water spinach and cotton

Turning rau muống (water spinach) into paper, Handle with Care documents the ongoing negotiation of the plant’s status in the U.S. as an invasive noxious weed. Wanting to re-establish foodways, some of the first Vietnamese refugees brought with them seeds of rau muống given its importance in everyday cuisine. As it began to flourish in backyards, the state began to regulate its cultivation, movement, and sale — perceiving it as a ‘threat’ to open waterways and the landscape. Presenting this history, the piece traces the administrative processes and authorities that render certain things native and allowed to exist, while others are cast as invasive and subjected to control and removal. On the other hand, it also seeks to present the instances of community resistance that emerged to declassify rau muống in Minnesota and most recently, Georgia.

Rau muống challenges us to become ungovernable as its spillages and cross-pollinations remain fugitive and defy containment. Taken altogether, the pieces collectively contemplate the displaced labors of feminized worldbuilding and care that obscure, evade, and alter colonial constructions of livability.

Thank you to XIA Bookstore, Gallery, and Cafe (Saint Paul, MN) for hosting the original physical exhibit in May of 2025 and to Marcus Lee for contributing the photography used in this digital exhibit. Thank you also to grant funding provided by the Mellon Periclean Faculty Leadership (PFL) Program and the Minnesota Historical Society. All views expressed are our own.